If I accept the argument of thought-provoking and prolific Allison Gaines, author of the July 5 Medium essay, "What is a Woman, and Why Does That Matter to So Many Americans?", I should not be asking the question which forms the title of both her piece and mine: “What is a ‘woman’?”

People who do ask this, says Gaines, "gatekeep womanhood for sick, twisted purposes."

By asking it, one, such as I, who considers “What is a ‘woman’?” a perfectly reasonable, and even timely, question, “reduces womanhood to sex”; a particularly egregious act, since “being a woman is so much more than [one’s] physical body.”

Additionally, by giving the common definition of the word woman — the one which has held preeminence in every human culture for 10 millennia: an adult human female, with female meaning “an animal whose body is organized for the production of an ovum” — I and others “work to exclude trans and non-binary people.”

But most of all, “asking someone to define a woman tells us two things about the asker. For starters, they do not understand the difference between sex and gender, and secondly, they want to argue about things beyond their comprehension.”

Well, Gaines may be correct on this last point. Unlike Ping, I know what sex is: Essentially, it’s everything which differentiates between the production of male and female reproductive cells, aka sperm and ova.

I don’t know what gender is, however. The definition seems to keep shifting. I’ve never heard the same one repeated, nor have I heard one, lately, which I understand. Nor does Gaines provide one in her article.

As for matters beyond one’s comprehension…well, those are exactly why we have questions.

What I do comprehend, however, is the following: I don’t want to exclude anyone from anything they’re due. I support the rights of adult trans and non-binary people to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Plus, I don’t think they should be mistreated in any way.

I mean, everything the author says in her text, about people who ask this question — “What is a ‘woman’?” — may be true. Personally, I think, quoting the Gershwins, “It Ain't Necessarily So.” But, obviously, her claims can be investigated, and will be, here.

And, finally, despite Gaines’ aversions, I see a lot with which to agree in her piece.

One thing that immediately jumps out at me, for example: The author, who also writes frequently and compellingly on race, notes how she always uses the noun people when speaking of racial “Blacks and whites” — i.e., Black & white people.

Her reason? She does this to avoid inadvertent dehumanization of her subjects; i.e., merely stating “Blacks & whites” leaves open the question, “What kinds of things are these ‘Blacks & whites?’” This is commendable, and her practice has also long been a one of mine, and for similar reasons.

Gaines also seems to disdain the emergent, butcher chart, parts-harvesting language — analogous to Kelly Eident’s snazzy, sardonic one-piece, above — which some have recently embraced for describing women and their reproductive activities.

By this, I mean terminology currently applied to both what many call cisgender women, and trans and other kinds of men. It seems the author affirms the value of gender-neutral language, which this terminology purports to be. Yet, still, she recognizes an ongoing debate regarding of what such language should consist.

For example, the term "chest-feeding" has recently surfaced. It’s used to designate the activity women’s breasts naturally do — produce milk for infants — but without stigmatizing trans women (born male), who do not possess these organs.

Or, "individuals with a cervix" reads as a way of denoting women who possess such internal structures by fact of birth, including trans men (born female). (Both groups are counter-balanced against trans women [born male], who, of course, do not have cervixes.)

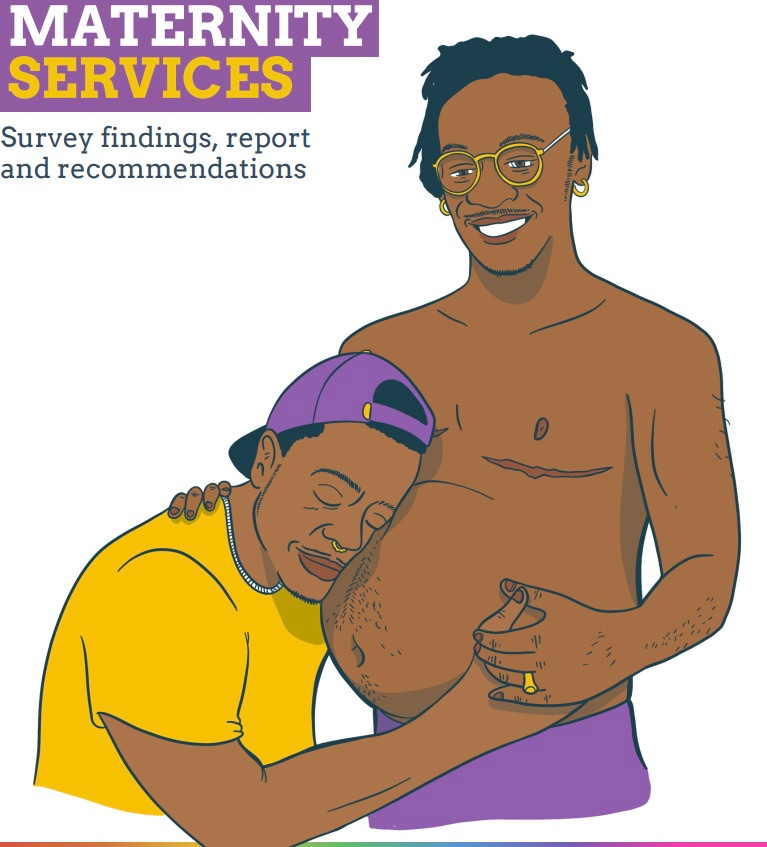

Or, this writer’s favorite reproductive neologism, “frontal birth,” designed to update the vaginal kind. The term appears in the UK-based LGBT Foundation’s recent report, Trans + Non Binary Experiences of Maternity Services, above. (So does “chest-feed.”) "Individuals with a cervix," on the other hand, comes from documents produced by the American Cancer Society.

“When we reduce women to their biological functions, we risk dehumanizing them,” says Gaines. I absolutely agree.

However, here’s where things get sticky.

A question Gaines’ contention raises, and one I’ve never heard addressed, is this: Do certain ideas within modern gender theory risk doing the same thing — dehumanizing women? Is such a thing even possible?

Here, I do not mean ideas undergirding extant controversies over whether:

• Children, in certain instances, should be given hormone-inhibiting drugs, like Lupron and Triptorelin, with or without parental consent

• Children, for any reason whatsoever, should be given radical double mastectomies of healthy tissue

• Males, who transition to females post-pubescence, should compete against females in sports

• Males, who transition to females, should be allowed in women’s spaces; bathrooms, changing rooms, shelters, prisons, etc.

• Males, who transition to females, should be allowed to intimately supervise females; e.g., in police or security “pat downs,” recuperative or long-term home care, etc.

• Etc.

Instead, I mean, beginning with, the notion people can change sex.

Can a man change into a woman?

Right off the bat, a few facts appear to be awesomely clear:

Number 1. This seems to be an eminently reasonable, scientific question; one whose affirmative return would form some basis for transgenderism, itself.

By this, I mean the following:

If a central proposition of transgenderism is, as it seems to be, “A man can change into a woman,” this fact, itself, infers the question — Can a man change into a woman?

In other words, a central proposition of transgenderism — “A man can change into a woman” — is the answer to the question, Can a man change into a woman?; one phrase is the other turned inside out.

This identifies the question as legitimate for anyone to ask, or, certainly, to re-ask; i.e., no reasonable person would ever maintain a question should not be asked because someone has already asked it. All questions are infinitely re-usable.

Number 2. On the face of it, this question — Can a man change into a woman? — also seems to be the kind of question to which one follow-up question might immediately, reasonably be, “What is a ‘woman’?

Or, said another, admittedly more complicated, way, “Into what are we asking whether or not a man can change?”

Again, this seems to be a natural question — a related question — which one might ask, in response to the first question, above. In other words, if a man can change his sex, he must change it into something. If that something is a woman, well, what is a “woman”?

In other words, one would need to ask, and know, “What is a ‘woman’?”, just to be sure that, having changed one’s sex, they’ve reached “their desired destination”; the state — “woman” — to which they were transitioning. Again, I don’t see why, in this context, such a question seems unreasonable, as Gaines asserts, so I will assert it is appropriate.

But, if so, this falsifies most, if not all, of the author’s contentions about this question — “What is a ‘woman’? — these being the primary focus of her article.

The End.

In other words, her piece lays out a variety of reasons, above, why she deems the question, “What is a ‘woman’?” improper.

For example, ending her critique, Gaines warns: “As we advance, be cautious of people who ask for a definition of a woman and instead question their intention for asking such a question”; a seemingly odd retort from a self-described “AfroSapiophile.”

However, what I have shown, by the above process, is this: The question, “What is a ‘woman’?” derives naturally from the propositions of transgenderism, itself; i.e., the phenomenon of transgenderism innately asks, “What is a woman’?”

Hence, to say the question is improper is to say transgenderism, itself, is improper.

This means, within the discussion of transgenderism, the question, Can a man change into a woman?, is, absolutely, always germane.

That said, what is the answer to the question, Can a man change into a woman?

Well, again, it seems the answer to this question is based upon the answer to the question, “What is a ‘woman’?”

In other words — and here, we will use the traditional definitions of the words “man” and woman,” merely for argument’s sake — if a “man” is an adult human male, and a “woman” is an adult human female, the question can otherwise be posed as, Can an adult human male change into an adult human female?

However, this question further reduces, based on the definitions of male and female. These are, again, respectively, “an animal whose body is organized for the production of sperm” and “an animal whose body is organized for the production of an ovum.”

This further clarifies the question, to read as follows: Can an adult human animal, whose body is organized for the production of sperm, change into an adult human animal, whose body is organized for the production of an ovum?

The best answer I can give is, “I don’t know.”

I’ve never heard of anyone saying such a thing is possible.

For example, in 2017, researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science, in Rehovot, Israel, concluded “there are over 6,500 protein-coding genes with significant [sex-differential expression] in at least one tissue,” of the 53 human tissues they tested. This sounds as though, were one to try and implement the changes alluded to above, it would at least result in substantial rewiring.

However:

So what?

• These changes, above, may not be the project of transgenderism; its end goal. If so, then these facts may be irrelevant to it.

Or, said in a slightly different manner: One way males might become females is by fiat; by simply declaring it to be so, then closely monitoring and controlling dissent regarding the pronouncement. (By analogy, this is much the way European powers claimed the New World, or the U.S. took over native territories.)

Fiat logic may be, at least partially, the rationale embedded in such statements as, “A woman is anyone who identifies as a woman”; i.e., like this statement, fiat logic is circular.

• It bears repeating: Mine is an essay about the language attendant to the question, “What is a ‘woman’?”, in Allison Gaines’ column; i.e., it is a textual critique. My objective is, and has been, to address her statements. (This is also why I only, here, above, speak to the “anyone who identifies as” definition of “woman”; it does not appear in Gaines’ text.)

But here’s where things get really sticky.

The question I raised before, but haven’t yet answered, though, is this: Do certain ideas within modern gender theory risk dehumanizing women…beginning with the notion people can change sex?

I’d actually never thought of this question, before; at least, not previous to writing this discourse.

Again, what prompted it, ironically, was Gaines’ own statement: “When we reduce women to their biological functions, we risk dehumanizing them”; a conclusion she’d buttressed with, again, this one: “Being a woman is so much more than [one’s] physical body.”

These led me to a new thought, in this context: Though not the only one, it could be argued one of the chief biological functions of women…is to appear to be women.

In other words, there is such a thing as appearing to be a woman. Further, this is something women tend to do, given, and via, their biology: Appear to be women.

Even more, looking like women is something in which women seemingly tend to have an interest, even a profound one. Women speak to this, even, in their songs, for example, and they keep doing so, over and over and over and over. (If it supports no other conclusion, the estimated $1.9 trillion a year women spend, globally, on clothes, shoes, and makeup may feasibly support this claim.)

Further, this appears to be a non-trivial aspect, not only of being a woman but, of being human: A sexually-reproducing species, like ours, in which women did not appear to be women — i.e., in which men could not differentiate women from men — would, quickly, cease to exist.

If appearing to be a woman is one feminine human function — as it may be — does a masculine act of reproducing feminine appearance risk dehumanizing women?

Also, to be clear: Am I saying, or suggesting, it does?

No. Absolutely not. I’m raising this as a question. I’m doing so because it’s a critique which appears to jump out of Gaines’ sober definition, as it intersects with these issues.

Further, I’d urge, it’s a question only women — ones born as such — can credibly answer, because it is them about whom the question is asked.

I particularly include gender-critical women here — many of whom have been slapped with the horrible, name-calling slur, “TERF” — as they are the women who may plausibly regard the inquiry most…well, critically.

Now, a final, essential question:

Is this essay “transphobic”?

It’s an important query. To comment on the phenomenon of transgenderism, yet be transphobic in one’s statements, besides being needlessly hurtful, would, of necessity, undermine one’s arguments.

Some will argue this work is transphobic because, they’ll say, I do not affirm certain dogmas and conclusions of the present-day trans movement, and/or, even worse, appear to question its hard-won convictions.

Some will say it’s transphobic because I’m writing about transgenderism, but not doing so with the language and terminology which typically accompanies the task. By this, they mean the lingua franca of alliance, commonly used to indicate support of and affinity for trans people.

Meanwhile, some will just not like my tone, deeming it too self-assured and non-deferential.

And, perhaps, others will say this writing is transphobic for other reasons, or for none at all.

Meanwhile, others, including, I expect, many transgender people, will say this essay is absolutely not transphobic.

As one might imagine, I agree with this final group, and deem the preceding criticisms superficial.

What I’ve done in this article is work to address the thesis question, “What is a ‘woman’?”, as it was framed in the prose of an able writer whose conclusions I did not share.

As opposed to hurling invective, attempting character assassination, or advancing similar forms of slander, I’ve spoken to the dignity of trans people, and worked to form an argument that I hope will raise thoughtful, new questions and verdicts.

There are many who accuse what’s often called “the transgender movement” of being highly, even extremely, antagonistic to inquiry or investigation in almost any form. However, I doubt this is the case, because any philosophical system so organized is likely to be, at its root, incoherent. I do not think transgenderism is incoherent.

I consider myself a transphile, and this document transphilic. I believe and support all of transgenderism’s true propositions. I support justice and correctness for transgender people. I believe they should be left alone, be free to go about their business, be helped when needed, and not mistreated.